In keeping with its objective of spreading knowledge about Indian Arts and Crafts, Paramparik Karigar conducts Craft Workshops and Lectures Demonstration by Master Craftsmen in schools and colleges across Mumbai, which aim to create familiarity and from there an interest in our rich Handicraft traditions.

Paramparik Karigar also partners with the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya Museum in Mumbai to hold similar workshops for the general public. On invitation our karigars have conducted workshops in institutions and at programmes across the country and even abroad. The workshops close to our heart have been those with social impact, like the Intense Workshops for underprivileged daughters of sex workers , the Workshops for the differently abled at Shraddha and the National Association For Blind. Now during this pandemic Paramparik Karigar has taken the workshops online. We are delighted to state that these online workshops have been well received and run to a full house. Registration details and other relevant information about our online workshops are available on our Social Media handles and on this website under workshops.

Our projects have always given us an opportunity to work and experiment with different mediums and art forms.

Our expertise lies in

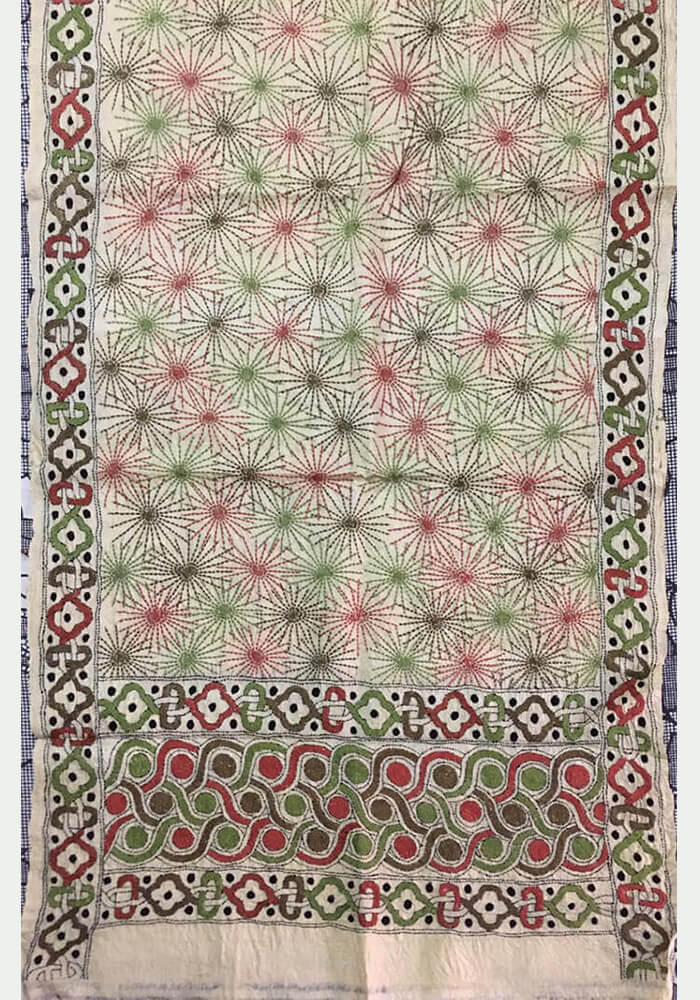

Dabbu Printing is famous amongst the Chippa community of traditional printers from Rajasthan. This craft is practiced around the Bagru and Sanganer regions.

This printing is originally worked in natural dyes, but nowadays chemical dyeing is also done.

All the motifs are derived from vegetable and floral forms and each bears a unique association with a specific Chippa community.

The Dabbu process begins with the collection and storage of mud from the local pond. The mud is made wet before being used, and it is then mixed with lime, gum, alum and jaggery. The fabric is washed to remove all the starch then treated with 'harda' and dried again.

The end printing is executed by applying a wooden block dipped in the 'dabbu' paste on the treated cloth. The fabric is then dyed. Depending on the design the fabric undergoes a second round of resist printing or washing which removes the mud paste.

The final dyeing imparts colour to the previously resisted areas.

This is a painting drawn on a piece of cloth known as 'Pati' or 'Patta'. The brush used is made of a bamboo stick and goat hair. Colours are got from natural herbs & plants. The Patuas of West Bengal are traditional artists who are specialized in painting narrative scrolls. They also sing the songs to accompany their unrolling. In olden days, the scroll painters would wander from village to village, seeking patronage by singing their own compositions while unraveling painted scrolls on sacred and secular themes. In West Bengal there are five folk forms of Patashilpa: a. Chau dance of Purulia b. Jhumur Song and dance of Bankura and Purulia c. Gambhira and Domni of Malda d. Baul and Fakira of Nadia e. Patachitra of Purba and Paschim Medinipur Today, scrolls by the young painters venture even further into current affairs, history and other subjects outside their tradition.

Patashilpa is one of the ancient folk art traditions of Bengal and dates back to over five thousand years. Their style is reminiscent of Mohenjo Daro and Harappa as also the Ajanta Caves. These scrolls are painted with vegetable dyes fixed with a vegetable gum on paper. The panels are sewn together and fabric from old saris is glued to the back to strengthen the scroll. Individual paintings may resemble single panels from same scroll stories, or independent images of wild animals and scenes from the artist's imagination.

This is a popular style of folk painting done in Rajasthan. Traditionally done on long pieces of cloth known as 'Phad', the narratives of folk deities of Rajasthan, mostly 'Pabuji' & 'Devnarayan' are depicted on the Phads.

The Joshi families of Bhilwara, Shahapura are known as the traditional artists of this folk art form. In Rajasthan, a tradition of wandering minstrels developed in the 14th century. The stories told were of Rajasthani folk heroes who were worshipped as demi-Gods. The large horizontal paintings that portray the epic lives of local folk heroes and demi-Gods in Rajasthan are popularly known as Phad paintings. These paintings have the task of representing a complex folk epic narrative which they achieve through their very specific style of representation. These paintings form a visual backdrop to all night storytelling performances.

The process of making the cloth ready for painting is an important aspect of phad painting. The cotton cloth is first stiffened with starch made of boiled flour and glue and then burnished with a special stone device called 'mohra' which makes the surface smooth. The artist makes his own pigments using locally available plants and minerals, mixing them with gum and water. Once the composition is laid out in a light yellow colour, the artist applies the traditional colour – red, white, green, blue, orange and brown.

Sanjhi, the art of hand cutting designs on paper, is a typical art form of Mathura in Uttar Pradesh, the legendary home of Lord Krishna. Traditionally, motifs from Lord Krishna stories are created in stencil and these stencils are filled with colours to decorate open spaces on the floors of temples during festive seasons.

The cutting process requires enormous skill, concentration and patience. The fine details are achieved with specially designed scissors. Of late, patterns of Mughal origin as well as more contemporary themes have been introduced to widen the repertoire. At one time this art was believed to be practiced extensively over Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Gujarat but now it survives only in Mathura.

Bagru is an important centre for hand block printing. The art of traditional hand block printing is practiced by the Chippa community. It is not only practiced in Bagru but also in Akola near Jodhpur and Bagh in Madhya Pradesh.

The unique method for printing uses a wooden block upon which the design is engraved. This carved block is used for replicating the design in a preferred colour on the fabric. 'Chippa Mohalla' (printer's quarter) is the area for textile printing. The three-centuries-old tradition of block printing is kept alive with the efforts of Bagru artisans. Keeping the convention, these artisans smear the cloth with earth from the riverside and then dip it in turmeric water to get the habitual cream colour background. After that, they stamp the cloth with beautiful designs using natural dyes of earthy shades. The motifs printed are large with bold lines, inspired by wild flowers, buds, leaves and geometric patterns.

As a matter of fact, Bagru prints are more famous for their exceptional quality of being eco-friendly. Even today, artisans use traditional vegetable dyes for printing the cloth. Like, the colour blue is made from indigo, greens out of indigo mixed with pomegranate, red from madder root and yellow from turmeric. Usually Bagru prints have ethnic floral patterns in natural colours. Bagru prints form the essential part of the block printing industry of Rajasthan. The village produces beautiful and unique bedspreads as well as other useful items

The Gara embroidery is a by product of the silk trade between China and the Persians in India. Parsi garas was introduced to Bombay by Sir. Jamsetjee Jeejeeboy, who brought back samples of Chinese embroidered silk from his journey to Canton. Parsi Zoroastrian textiles woven with self design was greatly influenced by various cultures from Persia, China, India, and Europe.The basic fabric used in the making of the gara was pure Sali Gaaj, Jacquard crepe, Gaaj satin. As Parsis are nature worshippers most of the inspiration is taken from nature in the form of flowers, birds, creatures, birds, trees, Pagodas as well as scenes from their daily life which is also depicted in their textiles.

These textiles were only woven on handlooms in the industrial city of Surat, in Gujarat. Due to Industrialization during the 1970’s all the handlooms were replaced by power looms and the weavers were jobless due to which the art of weaving this fabric is now lost forever. When a Parsi girl marries, even today there are 2 items that will mostly be a part of the trousseau, A gara saree and a Real Zari border, these are heirlooms passed down through generations and are considered collector’s item. A Gara is the symbol of the living heritage of the Parsi Community.

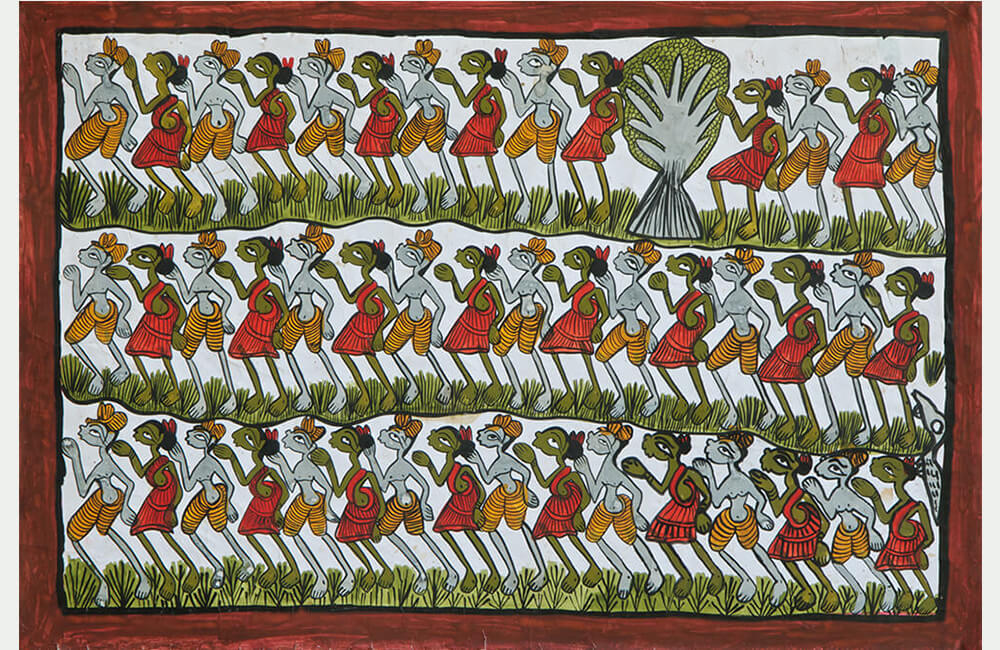

Rajasthan is well known for its beautiful Leheriya work. 'Leheriya' is found almost exclusively in Jaipur and is one of the most geometric and graphically vibrant forms of tie and dye fabric. Leheriya is one of the many variants of Bandhej, and is characterized by the colourful diagonal stripes and waves that resemble a 'leher', as the wave is called in Hindi. In Jaipur, daughters would be gifted leheriya saris as part of their dowry to symbolize the wedding vows as eternal and everlasting. Similar patterns would adorn the groom's turban. The sacred thread which is popularly used in various Hindu rituals is also influenced by leheriya work, with bright yellow lines across a red base. Dyeing is accomplished by the tie-resist method in Leheriya where the patterns are made up of innumerable waves. The material is rolled diagonally and certain portions resisted by lightly binding threads at a short distance from one another before the cloth is dyed. If the distance is shorter, then greater skill is required in preventing one colour from spilling into the other. The process of dyeing is repeated until the requisite number of colours is obtained. For a checkered pattern the fabric is opened and diagonally rolled again from the opposite corners, the rest of the process remaining the same. Several other items like turbans, Odhnis and saris with leheriya are liked and worn all around the year but carry a special meaning on and around the time of 'Teej' and 'Gangaur' festival and during the monsoon season.

n 1971, during the Indo-Pakistan war, some families migrated from the Sind province of Pakistan to settle in Western India. Some others went to Tharad in Banaskantha (Gujarat) and some to Ganganagar near Jodhpur. The Kutch and Tharad families excelled in Soof Embroidery.

Soof embroidery is a counted thread technique worked with fine solid-colour threads and darning stitch work on the reverse side of cotton fabric. The stitches that appear on the face typically are 2.5 to 5 mm long but only one fabric thread apart. The threads are counted just before the needle is inserted, and the most striking features are that the stitch is worked from the back of the material. It is a painstaking form of embroidery without tracing the motifs, and the artist's imagination depicts the infinite variations upon the fabric.

Soof Embroidery involves the use of geometric patterns. 'Leher' or wave is a common pattern. This art form is represented by highly stylized motifs. Most Soof patterns begin with a triangle and are full of rhythmic patterns and motifs depicting the artisans' lives. Peacocks and 'mandalas' are supposed to focus psychic energies. Several stitches are named in the local language to distinguish the patterns created and these are named as follows: Resho, Lad, Soof, Phalo, Chalangi, Ler, Sagar, Bato, Jali, Gantri, Goldo, Bakhkhio and Sankli.

Soof embroidery is used in making beautiful tablecloths, wall hangings, cushion covers, dress materials and various other items.

Woodcraft lacquer work is done by the wood crafting community at Nirona – Kutch. Though wood is beautiful in itself, man has tried to accentuate certain of its qualities by further ornamentation. One medium is lacquering in which countless designs and colour schemes can be executed. Lac medallions are obtained after heating a plant product. Lac is heated to a plastic condition, kneaded, colours obtained from local stores are added and drawn to be made into sticks.

Before applying the Lac, the wooden article is smoothened by rubbing with fine pottery powder, then put on a ‘lathe’ and rotated, while the Lac stick is pressed against it. The friction softens the Lac, which then is smeared all over. If more than one colour is to be applied, spots are left blank. Then more rounds are taken to cover up each spot with a different tint. It is fascinating to watch a Lac turner spin out his designs in various colours with a small sharp chisel. A marble polish is given by first rubbing with a bamboo edge and then with an oil rag.

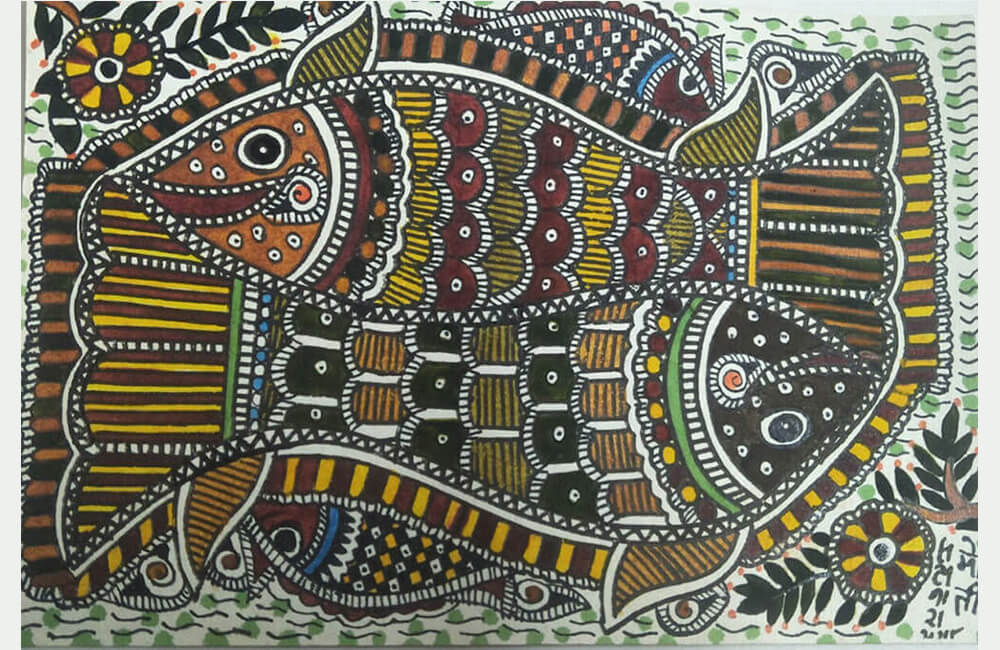

Mithila is also called Madhubani Painting, practiced in the Mithila region of Bihar and in the towns of Madhubani and Darbanga. The painting was traditionally done on freshly plastered mud walls and floors of huts. It is done with a broomstick and colours extracted from leaves and flowers.

The main themes are religious (Gods and Goddesses), nature (birds, animals, forest) and Social (day to day life).

During festivals and celebrations, women decorate their homes by drawing distinct patterns on the walls, ceilings and floors of their homes. This region has been exposed to many religious influences, thus Buddhist and tantric imprints on local motifs are visible. It was in the sixties, due to natural calamities, that the idea occurred to transpose the art onto paper, so that the paintings could be taken to other states and sold to collect Relief funds.

The beauty of Mithila Art lies in its painstaking detail. The painting is done on handmade paper which has been rubbed with cloth dipped in a mixture of water and the residue obtained from sieving cow-dung. The paper is then left to dry which makes it firm as well as free from insects. The brush used is a cotton-tipped broomstick dipped in colour pastes obtained from natural sources like the leaves of beans and mango tree, grass, 'parijat' flowers soaked in water, mehndi mixed with water of cow dung, skin of pomegranates and oranges. Traditionally the colours were obtained from flowers which were discarded from temples and pooja homes. The resin which is collected from the mango, neem or babul tree is mixed with water and added to the natural extract to make the colours thick. The resin also makes the colours fast and gives them a shine. There are different designs for various occasions and festivals, e.g. birth, marriage, holi, suryashashti, kali puja, durga puja, etc. Apart from their decorative purpose, they also constitute a form of visual education from which we learn of our heritage.

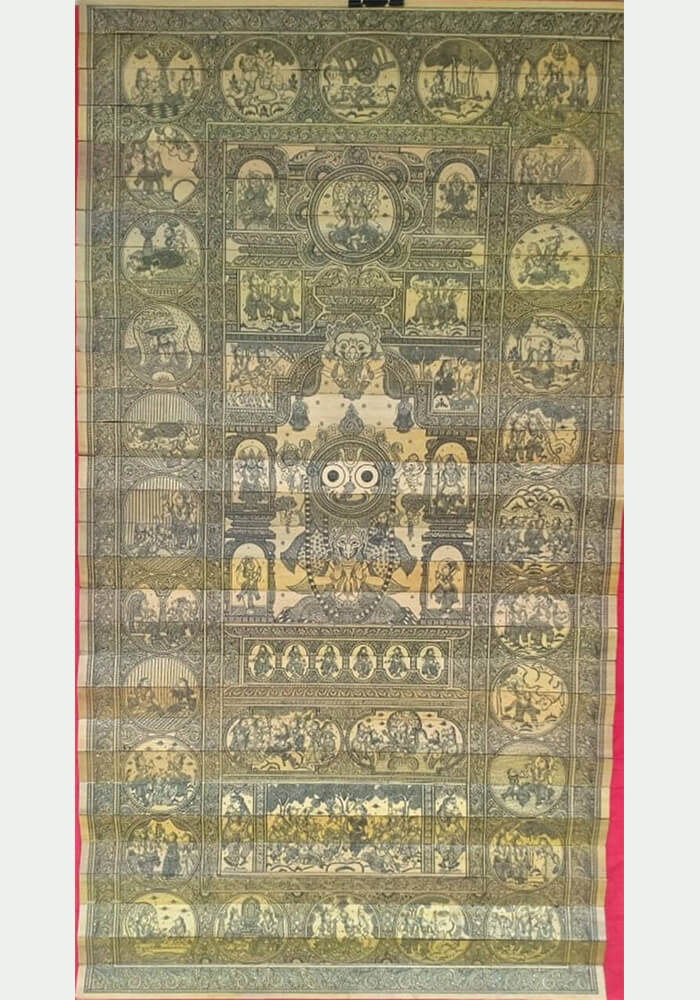

The folk paintings of Orissa have flourished around the great religious centers of Puri, Konarak and Bhubaneswar. Traditionally the painters are known as 'chitrakars'. Their painting, the 'pattachitra', resembles the old murals of that region, dating back to the 5th century BC. The best work is found in and around Puri, especially in the village of Raghurajpur.

Pattachitra is a traditional craft, where the artisans delicately paint on primed cloth or 'patta' in the finest detail. The 'chitrakars' (artists) prepare, what looks like a hard card paper using layers of old Dhoti cloth and sticking them together with a mixture of chalk and tamarind seed gum, which gives the surface a smooth leathery finish, especially after it is rubbed with a conch shell. The theme is sketched with a pencil, then outlined with a fine brush using vivid earth and stone colours obtained from natural sources, like the white pigment prepared from conch shells, yellow from orpiment, red from cinnabar and black from lamp soot. After completion, the painting is held over red hot charcoals and lac mixed with resin powder is sprinkled over the surface. When this melts, it is rubbed over the entire surface to give a coating of lac.

A recent modification in Pattachitra paintings is the division of the Patta into a row full of squares with the high-point of the story in the larger centre square and various events portrayed in the other squares. Themes usually depict the Jagannath temple with its three deities - Lord Jagannath, his brother Balabhadra and sister Subhadra and the famous Rath Yatra festival. These paintings were originally substitutes for worship on days when the temple doors were shut for the 'ritual bath' of the deity. Many Pattachitra paintings are from the ancient Indian texts based on Vishnu and Krishna. The paintings are of various shapes and sizes.

A few artists in Kutch practice hand painted pottery today. The locally available clay is thrown at the wheel to create pots of various sizes and shapes. The ornamentation of these forms is then done by the women folk of these potter communities.

Although the end product is simple, the craft process requires extreme dexterity and skills. The artisan is required to manipulate the pot with one hand while painting it with the other hand.

The patterns are generally geometric forms or stylized motifs that represent humans, birds, animals, plants and flowers.

The main production centers are the villages, namely Bhuj and Lodhai. The main articles produced are 'Matlo' (water pot), 'Gallo' (money boxes) and varied kinds of pots as well.

Pipli is a small village between Bhubaneswar and Puri in Orissa and is renowned for its brightly coloured applique work. Pilgrims coming to visit the Jagannath temple stop at Pipli to buy banners as offerings to the temple gods as well as small canopies for their domestic deities and for festivals. Pipliwork is supplied to monastic houses for their religious processions. In recent times, Pipliwork is used in making cushion covers and bedspreads and several items which are of contemporary use. Canopies and colourful sun umbrellas also showcase this bright and vibrant form of appliqué work.

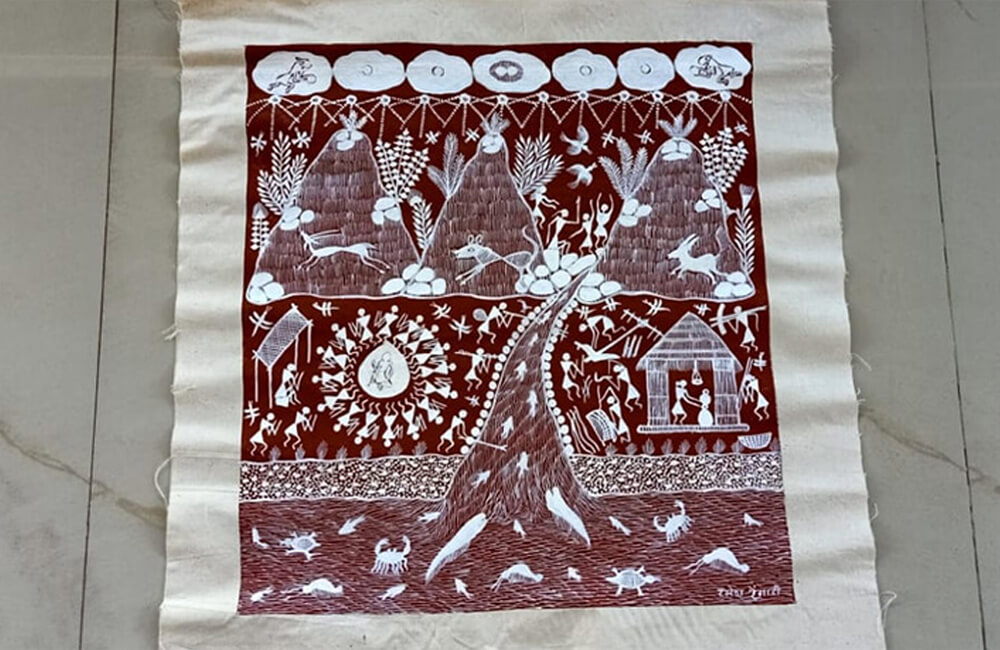

The Warlis or Varlis are an indigenous tribe or Adivasis living in the mountainous as well as the coastal regions of the Maharashtra- Gujarat border.

Warli paintings are a very rudimentary style of painting using basic geometric forms of circles, triangles and squares to adorn walls and floors. The circles and triangles come from their observation of nature, the circle representing the sun and the moon, and the triangle the trees and the mountains. The square seems to be a modern day adaptation to represent an enclosed space or piece of land called a 'Chauk' or 'Chaukat'.

Warli paintings are traditionally done with locally available 'Geru' (a red mud) and figures worked with a rice paste. The walls are coated with cowdung, mud and then with 'Geru'. Reed like sticks from the 'Baharu' tree was used as pens.

Scenes like hunting, fishing, farming, festivals, dances, trees and animals are represented with the mother goddess as a central figure.

However, today these are widely done using commercially available colors- mainly black, indigo, earthy mud, brick red and henna. Realizing that there is a growing demand for this typical art, the Warli's are now using this art form on cloth, paper, table lamps, saris and dupattas.

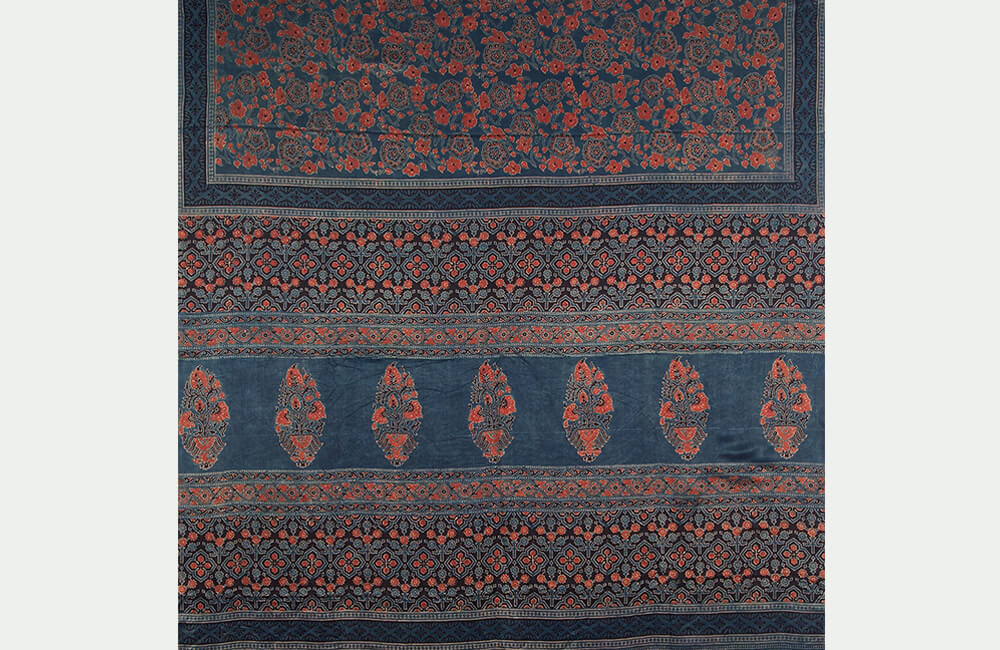

Ajrakh in Arabic refers to a moonless sky at midnight with the stars sparkling in the darkness. Literally, it could mean keep it for today (aj – today, rakh – keep) – it is believed that the more one delays in starting the next process of printing, the more stunning the piece turned out!!

It is practiced in three clusters – Dhamadka, Khavada in Kutch , Barmer in Rajasthan and Sindh, Pakistan. Here in Kutch, it has been mostly practiced by the Khatri community for over 9 generations and now the Harijan communities who were earlier workers with the Khatiris have gone on to being entrepreneurs. This printing technique uses wooden blocks for resist printing, where patterns are blocked with mud or lime. The preparation and printing techniques are lengthy, demanding and highly technical. Traditionally Ajarkh fabric was used by men as lungis and as safas (turbans).

It was worn by men of the Maldhari (cattle rearing / animal husbandry) communities of the region – Jat, Node, Dhingraja, Halepotra, Mutwa, Bhambhia, Sumra and Kurar. For the women, specific motifs were printed - for older women jimardhis and dhamburas; for the younger women hairdo badshah pasand, and limai for the widows. Earlier lungis and safas were printed in two parts (traditional handlooms were of narrow widths) and these two parts were hand stitched together, with different communities using different embroidery stitches to sew together the parts. Even today the Maldharis buy it as two pieces and sew it together. Currently the product range includes yardage for garments, bed sheets, table covers, sarees and dupattas.

Cheriyal art from Telegana can Traced back to the 12th century. A Cheriyal is a narrative scroll that is painted traditionally on Khadi cloth. The Cheriyal artists uses natural colours. White is obtained from sea shells, black from soot, red and yellow from stones, blue from indigo, skin tone from turmeric.Red is the predominant colour in a Cheriyal piece Mythological stories, local folklore and legends are commonly painted on Cheriyals

Lucknow has been and is even today the centre for Chikankari in India.

Chikankari, dates back to the Mughal era. Empress Noor Jahan is said to have introduced this embroidery to India.

It is one of the finest types of intricate embroidery, wherein motifs are created using white cotton thread using simple or inverted satin stitch, darn stitch, buttonhole, netting and applique work.

The materials used include Delicate cotton, Chiffon, Georgette and Rubia Fabric

Legend says that Mallika Noorjahan embroidered a design motif on a piece of cloth which was then converted into an inlay work on her father Hmadulla's tomb in Agra. This tomb is one of the best specimens of Moghul Art in Agra.

Like Zardosi and other intricate embroidery, complicated and detailed Chikankari embroidery, too is done by men. Earlier this craft was confined to the "Zanana" – ladies. Girls embroidered articles for their dowry, or to embellish their outfits. Male members made articles for the house like bedspreads, table covers, thaal covers, Dupatta, Saris, Royal Robe dresses and so forth.

In Madhubani, Bihar, Papier-mache articles have been made for many generations and has been handed down from mother to daughter. Papier-mache toys and dolls are modelled on folk tradition which has continued to find vibrant expression in their work. This craft is light, cheap, durable and adaptable for making decorative bowls, vases, pots, jars, frames, masks, exotic beads, earrings, bangles and trinkets, containers and boxes for storing grains, fruits, dry fruits and also for making jewellery and bangle boxes. Products made by papier Mache have a raw earthy appeal.

In Madhubani, papier-mache, the ancient eco-friendly craft is made by mixing paper pulp with 'Multani Mitti', 'Dardmeda' powder obtained from the local Dardmeda plant, the juice of neem leaves and methi. The object is smoothened and given shape and dried. More pulp is added to give the right shape while in a moist state. The object is then polished and dried. When completely dry, it is coloured in vibrant hues using minerals, roots and flowers. No tools are used, they are hand painted with figures like elephants, gods and goddesses and birds. The Hindu goddess 'Durga' in papier mache is much in demand during local festivals.

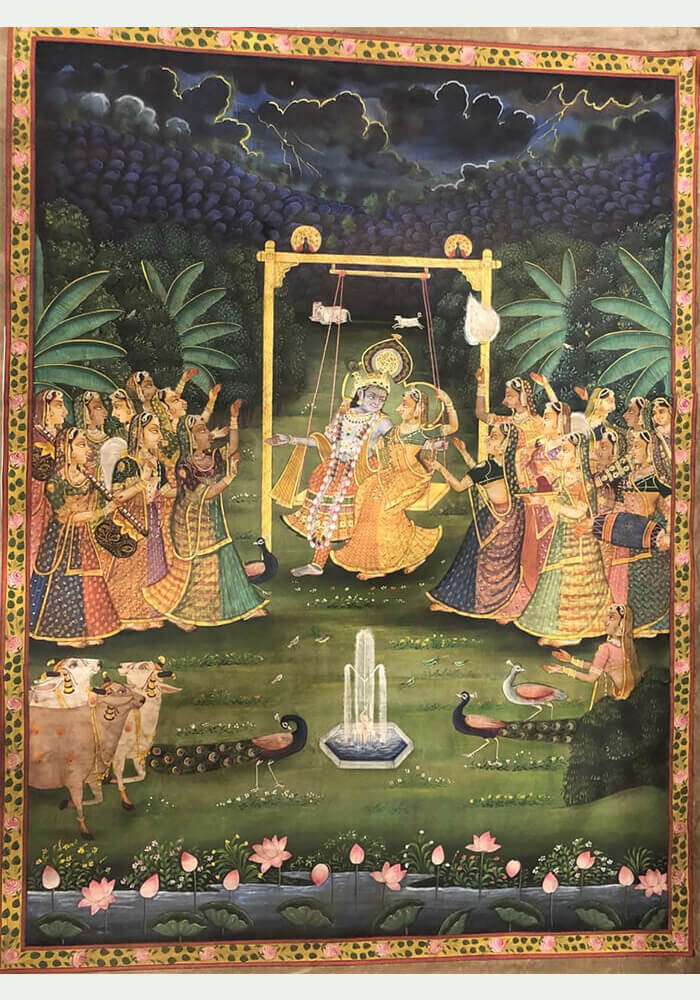

The word Pichhwai is derived from the Sanskrit word 'pich' meaning back and “wai” meaning hanging.

Pichhwai is an intricate painting, done mostly on cloth or paper, portraying Lord Krishna.

This art form has its roots from the holy town of Nathdwara in Rajasthan, in India. Lord Krishna is shown in different moods, postures, and attires. This ancient art form has been passed on from generations to generations. A Pichhwais, other than its artistic appeal, also narrates tales of Lord Krishna pictographically. These artists mostly live in 'Chitron ki gali' (street of paintings) and 'Chitrakaron ka mohallah' (colony of painters) and is a close community. Many times a Pichhwai painting is a group effort, wherein several skillful painters work together under the supervision of a master artist.

Pichwai paintings are works of arts that are used to adorn the walls of temples. The Pichwai style is from the Nathdwara School and is identified by characteristic features of large eyes, broad nose and a heavy body similar to the features on the idol of Shrinathji. While the paintings depicting summer have pink lotuses, the paintings depicting ‘Sharad Purnima’ are of a night scene with the bright full moon. Festivals such as Raas Leela, Holi, are also themes that are often depicted. Sometimes rich embroidery or appliqué work is used on these paintings. Enclosed in a dark border, rich colours like red, green, yellow, white and black are used with a lot of gold decorating the figures. On a starched cloth, the painter first makes a rough sketch and then fills in the colors. Traditionally natural colors and brushes made of horse, goat or squirrel hair were used. The use of pure gold in the paintings adds to their value and charm and it may take 3-4 days to just prepare colour from pure gold.

Bandhani, from Gujarat represent the craft of tie and dye. With the ancient art being practiced in many places in Gujarat, each region has its own special design and colour schemes. The bandhanis of Jamnagar and Bhuj are distinctive in design, craftsmanship and ornamentation. The dyer first bleaches material like cotton, silk, georgette, crepe or satin to prepare it for the absorption of the dyes. He then folds the cloth two or four fold, and prints the designs in 'geru' (red clay) mixed with water. He ties a thin thread on the lines of the printed design after raising a small part of the fabric.

The textile is then dipped in the first colour which is light. The tied areas retain their original colour. This is repeated throughout the fabric. During the second dye process the areas that need to retain the colour of the first dye are securely tied for resistance and the cloth is then dipped in a deeper colour. The process may be repeated for several colours. When the fabric is ready, it is washed to remove the excess dye, but the ties are not opened till the buyer wishes it. When opened, the cloth remains evenly embossed at the tie-dots and generally shrunken due to tight tying. Aspecial fabric for a bride's marriage called 'Gharchola' is tiedyed, often in figurative patterns arranged in square compartments created by brocade or gold or silver embroidery. Another traditional design is the 'Bawan Bagh' that is fifty two blocks. Each of the blocks has an unique design, with no design being repeated on the fabric. Bandhani odhnis, household linen, ties, scarves and lampshades are popular items.

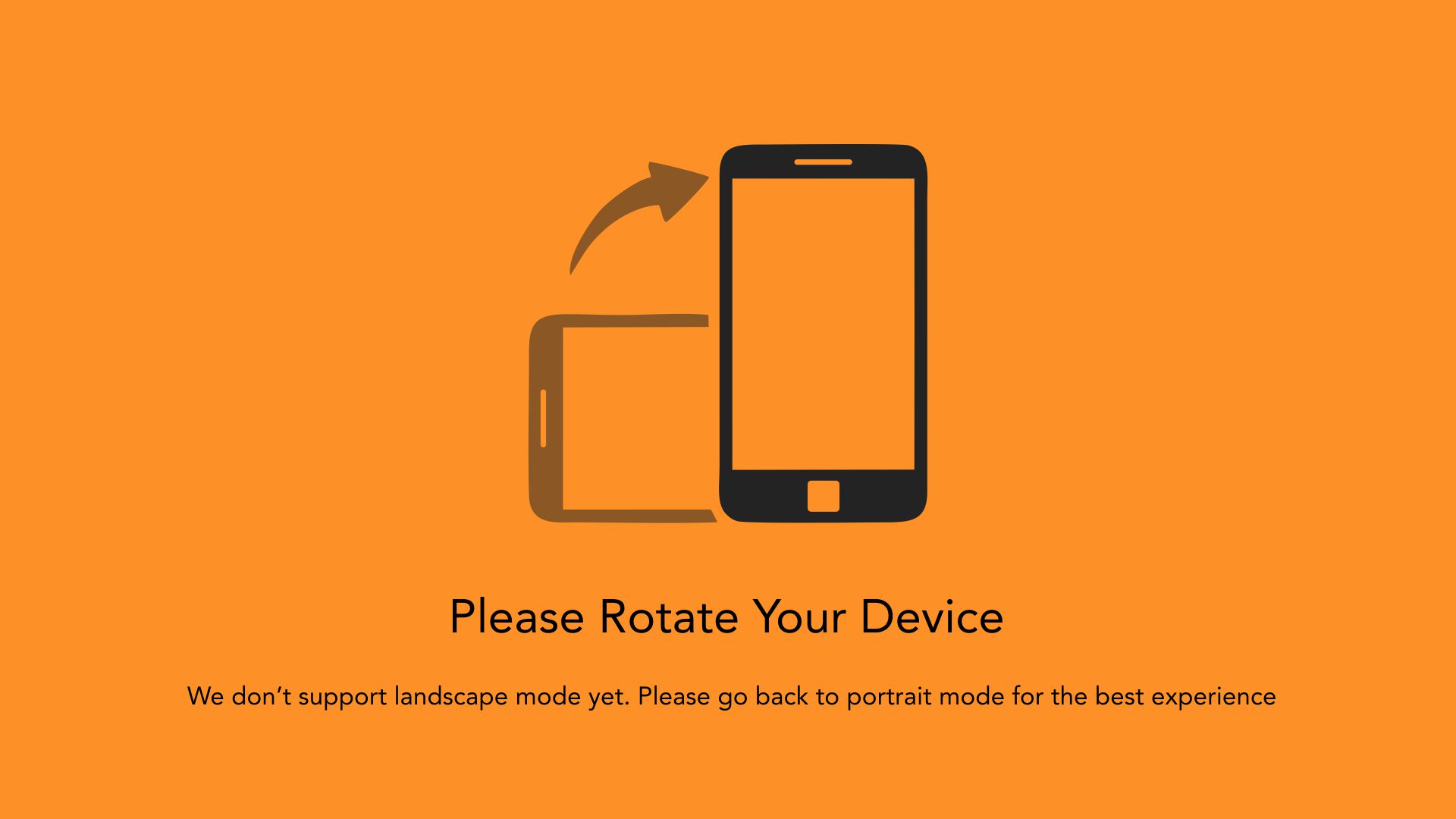

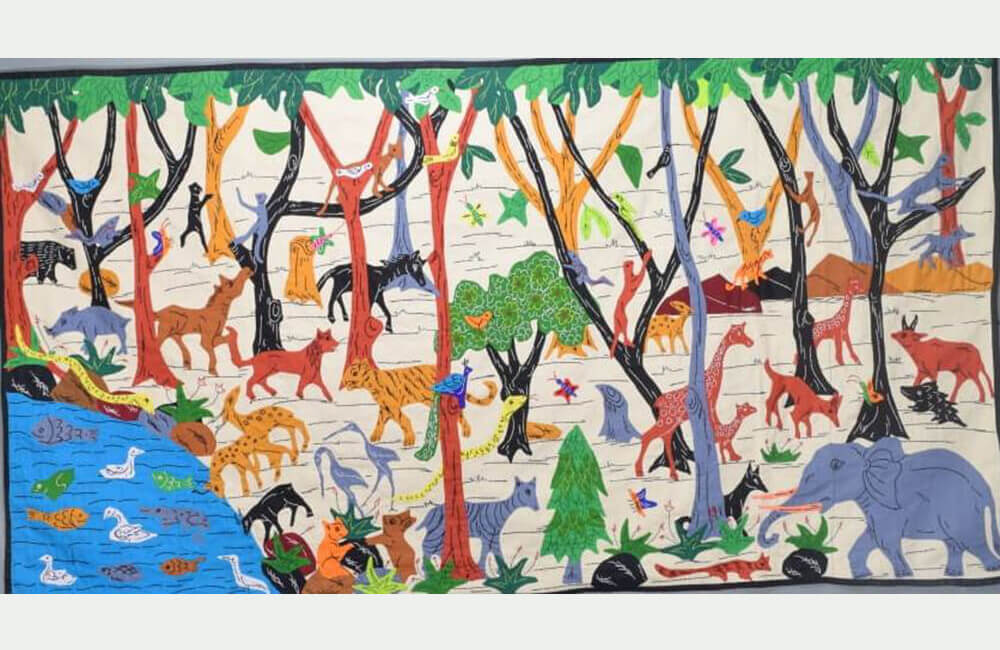

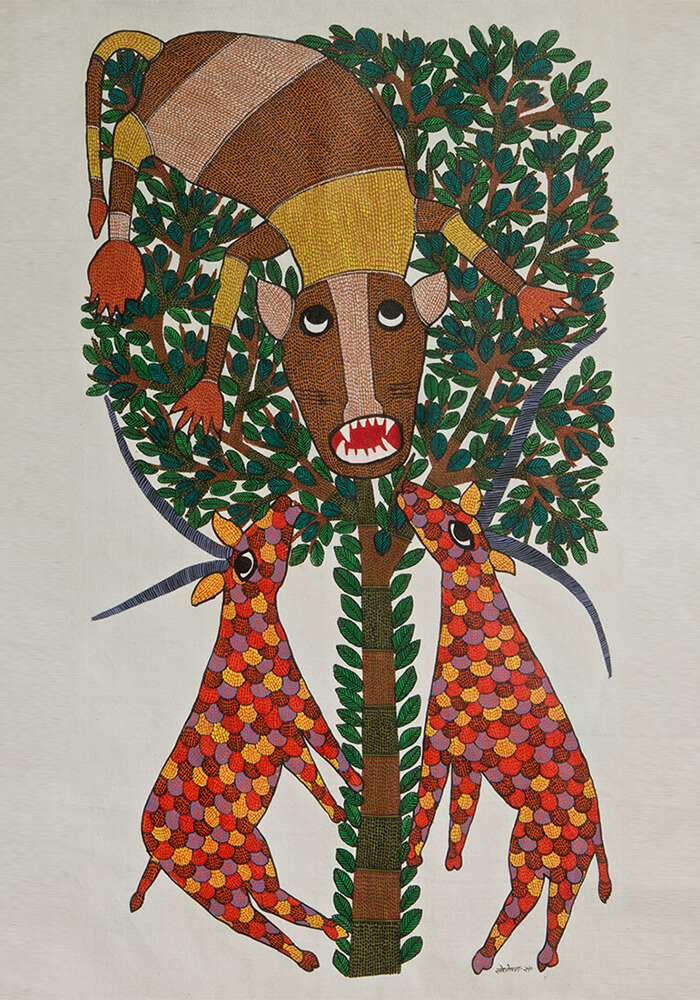

Geographically, the Gond territory extended from the Godavari in the south to the Vindhyas in the north. This art form is popular among most tribes in Madhya Pradesh and it is particularly well developed as an art among the Gond tribe of Mandala District. Gond wall decorations are made with a thick stick dipped in mud or clay mixed with chaff and water. When a house is under construction, the mud wall is kept damp for patterns to be imposed on it, which is then covered with cow dung or lime. The area may be sub-divided into panels by broad bands enhanced with geometric motifs. Within the panels, a design is carved with geometric patterns, animals, human figures and flowers patterns which are formed of interesting circles. Spirals and circles are also enhanced with alternate triangles.

In all these paintings there is a basic simplicity. They appear without anatomical details, and move in silhouettes. A simple impression of a pair of wings turns gradually into a geometric figure. A fish is symbolized by bones, a tortoise by its flippers. The former stands for fertility, while the latter for stability. Designs in white or red wash on the floor ensure security of the house. Blue, Yellow, Black are used in contemporary as well as traditional art. Local deities, cock fights, forest scenes, agriculture, weddings and other visuals find a significant place in Gond tribal art.

The Andhra Pradesh Kalamkari evolved with the patronage of the Mughals and the Golkonda Sultanate. Kalamkari art was once called 'Vrathapani'. There are two distinct styles of kalamkari - The Machilipatnam style and the Kalahasti Style.Machilipatnam style is made at Pedana near Machilipatnam.

Kalamkari is the art of painting on cloth and derives its name from the word 'kalam' meaning pen or brush. Traditionally, Kalamkari paintings were used to decorate temple chariots used in religious processions or stretched behind the idols of Gods. The designs usually have a main central panel and are surrounded by smaller blocks arranged in rows which depict the major scenes from a legend. It may also have verses from original texts written in black ink beneath the rows.

Traditionally, the craftsmen of Srikalahasti painted stories and scenes derived from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, which include the story of Krishna and themes from the environment like the Tree of Life.

The cloth to be painted is dipped in a mixture of milk and 'harda' and dried in the sun. The design is outlined on the cloth with a bamboo sliver using 'kasimi' - a black dye made from iron filings and jaggery. The interior of the design is then painted with various natural dyes one after another, each involving a laborious process of application and washing. Red colour is obtained by painting the relevant part of the design with alum, washing in running water and then dipping in a dye of madder.

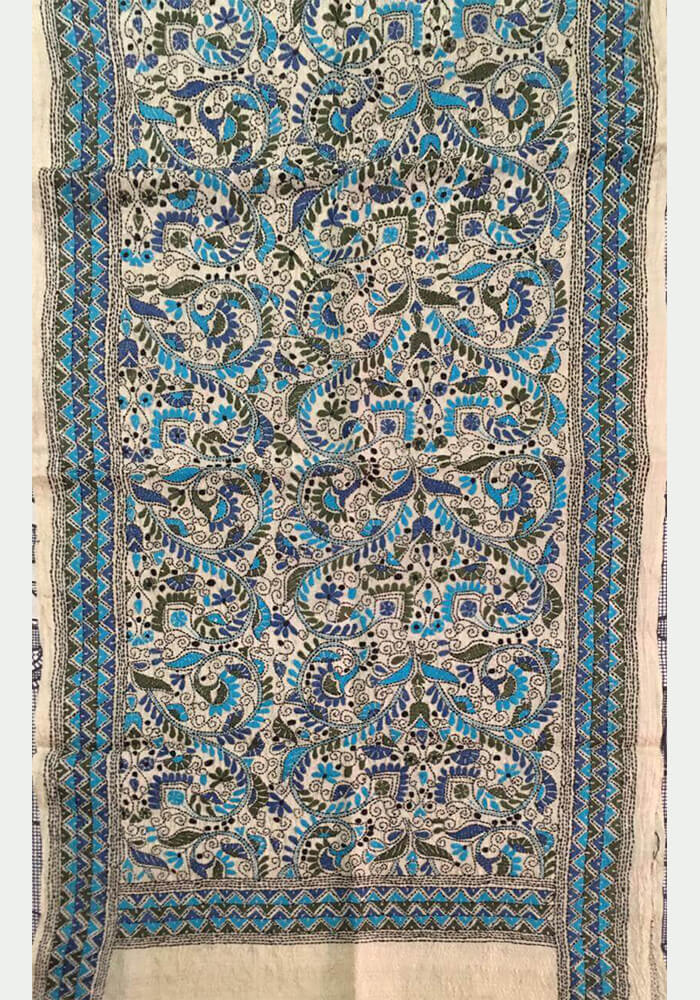

Kantha is the name of an embroidery and it has somehow become synonymous with the beautiful Bengal Kantha Silk Saris. Kantha, a patched cloth, is a running stitch worked on a 'lep'. Originally Kantha was used to join layers of old saris to make quilts. The women of Bengal created these to make a light blanket or bedspread. The Sanskrit word 'kantha' means 'rags'. Legend links their origins to Lord Buddha and his disciples who covered themselves with garments made of discarded rags that were patched and sewn together. Historically kantha was never made for money and in its simplest form kantha was invented out of necessity. Pieces made in varying sizes were spread in the courtyard to lay a newborn baby. Light covers were used by adults as a wrap on winter mornings.

Old white Saris or dhotis are layered and sewn together at the edge to prepare the fabric. Coloured threads are painstakingly extracted from old sari borders and used for the actual embroidery. Geometric, floral and, figurative designs are surrounded by rows of intricate borders in a darn stitch which recreates the woven sari border. Finally, the background is covered with minute white quilting stitches encircling the designs and giving the Kantha a rippling effect.

Today Kantha has evolved as embroidery on saris, dupattas and even bedspreads and on new material, without the second layer. Apart from the traditional designs, new designs based on 'Alpana' have been added. The vibrant and decorative motifs resulting in breathtaking designs, helped Kantha embroidery get a foothold in urban groups.

The leather puppets of Andhra Pradesh trace their origins back to around 200 B.C. They were used for shadow play by troupes that travelled the countryside. A special orchestra accompanied the puppeteers and the movements of the puppets were synchronized to the sounds of the music.

Leather puppets are made out of the hide of goat, deer or buffalo. The hide is treated with indigenous herbs and oiled and pounded until it is translucent. Parts of the body are drawn on the hide and then cut out and joined together by a thick knotted string. The skin is painted with bright colors using vegetable dyes.

Bamboo sticks and Palm leaf stems are used as rods for the central support. The female puppet has extra joints at the head and waist for extra mobility while dancing. Holes are punched in different patterns to denote jewellery and costumes. The piercing, the colouring, the dress - all have special meanings and are still done according to tradition. The costumes and jewellery are based on 'Yakshagana' and 'Kuchipudi' traditions.

Along with making leather puppets, the craftsmen have diverted their craft into making lampshades and decorative items for daily use.

Palm leaf etching was founded by the skillful people of Orissa decades ago and this ancient art is a style practiced in the villages of Orissa especially in the artist village of Raghurajpur and Chitrakarasahi. The paintings begin with a selection of palm leaves which are sun dried and then kept in the shade for a few days. These are then cut into thin strips of various sizes. With the help of an iron stylus, designs based on mythological themes are etched on to the palm leaves. The etching requires a lot of expertise to make sure that the pressure applied toward the etching is precise and appropriate. Etching is done with an ink like paste obtained from burnt charcoal and coconut shells. If the figures have to be in colour, engraved portions are rubbed and filled with herbal colours. Rectangular strips are tied and strung together much like the folding of Japanese fan, which when opened reveals the story to be conveyed.

Intricate panels, which reveal the artists' ability to paint in even a very small area, is one of the reasons why this is an absolutely fine art form and also much appreciated throughout the world today. Palm leaf inscriptions and recording horoscopes have been developed into a fine and precise art by the master craftsmen. Major literary works like the Mahabharata were originally inscribed on palm leaves. Even the later copper plate inscriptions were first etched on palm leaves.

Pottery is perhaps the oldest craft in the world. Traditional folk pottery has always been a part of Indian life and ceremonies. From pre-historic times, there has been an abundance of beautifully fashioned utilitarian pottery. It is one of the most ancient crafts surviving today. Different varieties of pottery like red, black, buff and gray were often painted with black and white pigments or decorated with geometrical incisions. Domestic pottery comes in a bewildering profusion of attractive shapes and sizes. The process of pottery involves modelling, shaping of clay, drying and firing. Clay can be categorized as primary clay, which include china clay and bentonite and secondary clay which include common clay, red clay, ball clay and fire clay. The potter throws the painstakingly kneaded clay on to the centre of the wheel, rounding it off, and then spinning the wheel around with a stick. As the whirling gathers momentum, he begins to shape the clay into the required form. When finished, he skillfully severs the shaped bit from the rest of the clay with a string. Though the firing is done in an improvised kiln, the quality and beauty does not get affected. Intricate glaze is made from a mixed composition, fired to form a vitreous material with glazed surface, and then coloured by different mineral substances.

Pottery is generally classified as earthenware, stoneware and porcelain, in relation to the clay used and the firing temperatures.

Kantha is the name of an embroidery and it has somehow become synonymous with the beautiful Bengal Kantha Silk Saris. Kantha, a patched cloth, is a running stitch worked on a 'lep'. Originally Kantha was used to join layers of old saris to make quilts. The women of Bengal created these to make a light blanket or bedspread. The Sanskrit word 'kantha' means 'rags'. Legend links their origins to Lord Buddha and his disciples who covered themselves with garments made of discarded rags that were patched and sewn together. Historically kantha was never made for money and in its simplest form kantha was invented out of necessity. Pieces made in varying sizes were spread in the courtyard to lay a newborn baby. Light covers were used by adults as a wrap on winter mornings.

Old white Saris or dhotis are layered and sewn together at the edge to prepare the fabric. Coloured threads are painstakingly extracted from old sari borders and used for the actual embroidery. Geometric, floral and, figurative designs are surrounded by rows of intricate borders in a darn stitch which recreates the woven sari border. Finally, the background is covered with minute white quilting stitches encircling the designs and giving the Kantha a rippling effect.

Today Kantha has evolved as embroidery on saris, dupattas and even bedspreads and on new material, without the second layer. Apart from the traditional designs, new designs based on 'Alpana' have been added. The vibrant and decorative motifs resulting in breathtaking designs, helped Kantha embroidery get a foothold in urban groups.